As human beings we innately crave that winning feeling and we significantly enjoy the gratification we take from our assumptions being correct. These general instincts limit our methods of learning as they encourage debate, a narrow and competitive form of discussion that usually ends with a winner and a loser and little in between. The defining issue with this method of learning is that despite whether you seemingly win or lose a debate, you will very rarely change the position of the opposition, both sides tend to remain concrete and there the learning experience abruptly ends. Instead, a learning process through dialogue where there is no winner or loser but a collective of learners interacting, exchanging ideas, listening and changing assumptions must be encouraged. This is called a Dialogic Learning Group (DLG).

What are the Principles of Dialogic Practice?

A DLG as a dialogic reflective practice is a key organisational development method, the purpose to provide a forum of mutual support. It encourages challenging the learning and development of every participant in the group and to provide comment, feedback and assessment of the work being undertaken.

The basic principles of dialogic practice are essentially three-fold. One is an assumption that interaction done well creates knowledge, so in effect the sharing of ideas creates the opportunity for new ideas to come together. Two is the hearing of others, which is fundamental to the process of change itself. Three, culture change in this sense being a change in the underpinning of assumptions. So, the more we interact the more we create shared knowledge and to create shared knowledge you must hear other people well. Put those two together and this tends to move the underpinning of assumptions. Ultimately, what you start to see is the shift of basic patterns of cultural assumptions within a group or an organisation.

The Necessity for Dialogue Over Debate

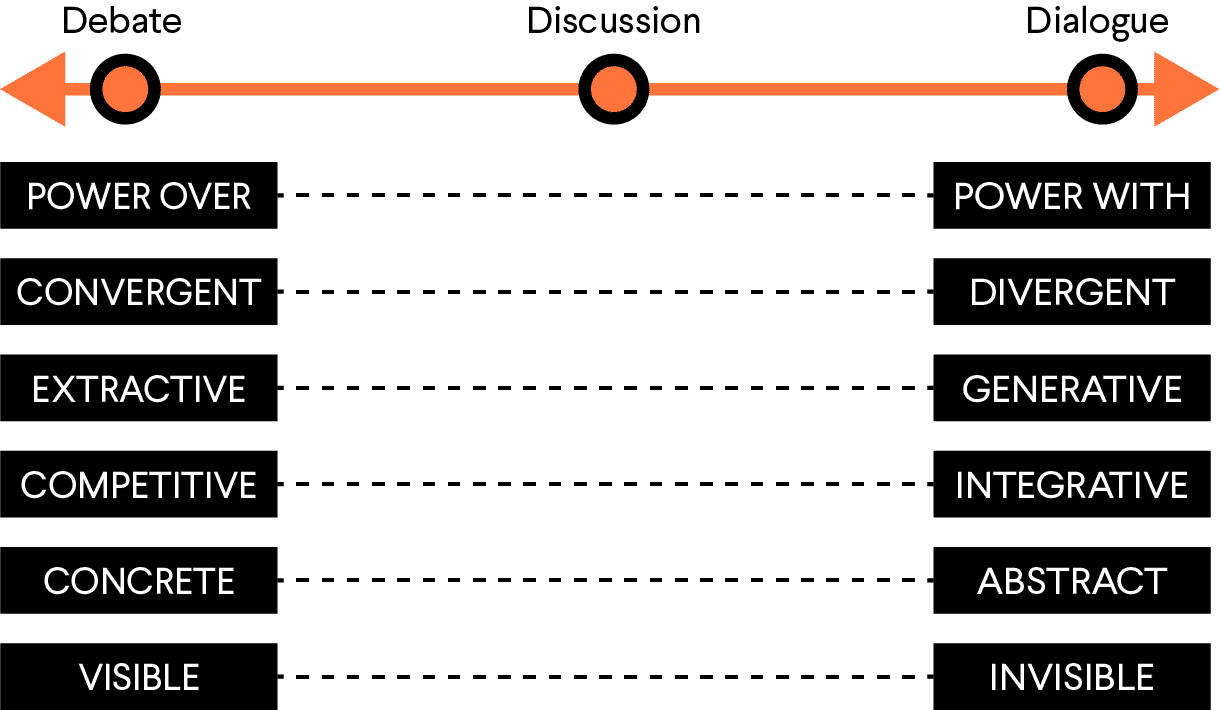

What is the difference between a debate and dialogue? Both are similar concepts where two or more parties engage in discussion but both have significant differing elements within their concepts. We begin with debate, where people compete on whose got the right idea, the power over the idea belonging to either you or me. The argument starts to converge around smaller points of difference with the intention to extract a win or a loss. Debating is a competitive process; the arguments tend to be very concrete and very visible in the minds of everyone. Usually there is a winner or a loser, visibly in our own minds we want to come out on the right side of the argument.

In contrast, the process of a dialogue is totally generative. People come out of dialogue with the basic assumptions that they do not necessarily have a defined end position, in fact they set out not to start with this. Most conversations have a defined position before they begin and it is rare to move people’s attitudes that much. Dialogue is disciplined in that sense, knowing and understanding your own position is partial to the intended result. You are then looking to generate divergent and different views of what the outcome could be, or what the idea is, or what the understanding might be. Fundamentally, we are trying to integrate abstract ideas and come up with something that is currently invisible to us.

Unlike debate where usually our assumptions are relatively concrete, in dialogue the first thing you must do as a personal discipline is to be able to put your assumptions to one side. This implies we even know what our assumptions are in the first place, which often we do not. One of the key elements of dialogue is we put our assumptions out there so people can respond and share theirs. This opens the field, broadening out and exploring rather than narrowing down and competing.

Potential Issues?

It can appear in dialogue that the larger voices are doing more of the talking, so some may assume that they perhaps benefit more than those who are more inclined to just listen and reflect. This is somewhat untrue as a lot of dialogue is non-verbal. You can be in a dialogue just by listening and a lot of the time what you will find is that social introverts are very good at picking the line of argument amongst louder, extrovert-like types throwing around their ideas. It is a real skill in dialogue to be able to map a path and join the dots as you go along. In fact, one of the more significant parts of dialogue is the reflection and thinking and the non-verbal part of dialogue that creates the meaning in the dialogue. The more reflective, or strategic types of thinkers will often be the ones who find the pattern that the group can then build around.

In dialogue you must expect that you might not originally get on well with another participant. When someone wants to challenge our assumptions we are naturally inclined to find it uncomfortable. However, it is not exactly all about the other person, it is also about you and how you respond. The whole point of dialogue is to get out of your comfort zone, even to the extent where you are very deliberately looking to engage with people that make you feel uncomfortable. Sitting down with the people you do not necessarily get on with is a good discipline, if somebody looks to challenge your assumption and you let it irritate you, it is you doing it to yourself and you will not benefit from the dialogue.