In an ever more multi polar world our concepts of culture are evolving. In progress now is a shift, away from pre-eminently western ways of understanding the world towards worldviews that include diverse eastern and southern perspectives.

In this world, the ability to ‘read’, see and sense these varied perspectives and respond to them, and give them equal validity and respect, will be an essential attribute of the globally effective executive. Indeed, the ability to flex between them, to ‘be’ in another culture, view and look out from it will perhaps be the most in-demand competence of future employees in the digital world.

Perversely, we tend to be inculcated with mind and world views that encourage the reverse of these abilities. From national cultures and norms, beliefs and other cultural signifiers, we are programmed to identify ‘in’ and ‘out’ people, favouring one over the other. We go to war in the name of values, and we discriminate and victimise in the name of (our) progress. Research shows that, in response to globalisation, communities are holding onto ever more localised cultural norms and behaviours (Rajan, 2019) There is perhaps a crisis of confidence surrounding the issue of culture, one that is evidenced by increasing localism, identity groupings, and even personal stress and distress around the topic of life purpose. In this paper, I am opening a dialogue that I hope you will join. I will explore and suggest some of the signifiers of cultural intelligence, the term I will use to describe this future human capacity for multi-polarity in the context of globalised and virtualised worlds of work. From this paper I hope will come other contributions that enable us all, whether from first, third, old, new or developing worlds, to recognise and structure those future attributes that will bring us all to a universal world, of respect, harmony and equal value.

In the beginning

In the beginning was the lone human in Plato’s cave. Dragged into the sunlight and confronted with different realities, he wanted to return, down to his dark cave. Return to the darkness and the shadows of things behind him that hitherto he had taken as reality. What was not known could not be true; what was known was a comfort, making the unknown unwelcome, unnecessary to know (Jowett, 1941).

Recognising this, we perhaps recognise the trap that education can fall into. In principle a means of enlightening and liberating human minds, it is all too often a vehicle for entrapment. Think of our national ‘stories’, most a refinement of a refinement of something that may have never actually happened as we now think. Think of the history you are taught, of the uncritical assessment of your own culture compared to others that your country, organisation or group may be at odds with. Education, the great potential enabler, is also a fabulous potential political and cultural restrictor.

Humanity has entrapment seemingly built into its social DNA. Michael Mann (1986) describes religion as humanity’s first cultural process for uniting disparate small communities. In the act of imposing this new thing called religion, he argues, power structures, based on created and imposed beliefs and the education of proscribed practices, became the signifiers of the powerful and the tools of behaviour management from a distance.

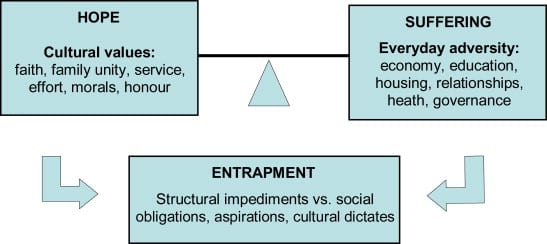

Eggerman et al (2010, p71) discuss how, in the context of resilience in post-conflict Afghanistan, cultural values and root beliefs “demonstrate that culture functions both as an anchor for resilience and an anvil of pain”, offering both the chance for hope and the linkages to entrapment and limiting social beliefs.

They suggest a model of interaction between hope, suffering and entrapment, showing the complex interactions between the various facets of culture at a meta level (education, governance, economy, housing etc) and at the micro and community levels (faith, family unity, morals, effort, social obligations, aspirations, cultural dictates etc):

Recent events in the American Capitol building, and the associated social media groupings that have sprung up, some with quite fantastic propositional beliefs, are great examples of how culture can both liberate and entrap simultaneously. Having worked in developing countries I have seen and heard at first hand the apparent fatalism that confronts these interacting forces. Life is life, as an East African friend says. This is perhaps more of a recognition of the ever shifting balance between hope and suffering that confronts most people outside the developed world. Far from fatalistic, it seems rather a simple description of the painful pivot that they are often confronting.

Language plays a part. It is interesting that, from Plato’s cave onwards, dark is down, light is up. Wrong is descent, right is ascent. The exposure effect of common cultural and linguistic norms is to habituate the users and, in doing so, inure them from exposure to other habits and norms (Persson, 2020). In an entertaining article, entitled ‘The fundamental problem of philosophy: its point’ Persson enters into a lively discussion of how we can and do adopt fallacies of ‘wishful thinking’ as truths, when they serve us. He talks about how this can translate into fallacies about ourselves and our capacities (overconfidence bias) or even our ability to get things done (planning fallacy). I recommend the article.

What all these contributors and many others point to is that we take on meanings that, well, sometimes have no meanings, other than to ourselves. We then act as if those meanings are truths and build a case for and against others dependent on whether or not they are supportive of our truths. We ‘like’ similar views, we engage with them les and less.

A delegate asked me a question recently; why do I feel more stupid at the end of this discussion than I did at the beginning? My reply was, because we are questioning things. This is the heart of cultural intelligence.

Open up, engage, be free.

Did you ever have parents, teachers or friends who said, apropos of something or another, you’ve got to have an open mind? Sure, it is a good thing to have. It is also, I suggest, close to impossible to attain continuously. A key part of openness is recognising how bounded we are. My work over recent years has often meant encountering incredibly boundaried thinking, masquerading as principle.

If we are to explore the phenomenon of cultural intelligence, we should change the nature of the challenge. What we should aim for is to prise open a corner of our mind here and there sufficiently to be able to listen and absorb intently. It will snap back afterwards. It almost always does. But for the period we have lifted the veil, we are more free than we were.

So, let’s have a priseable mind. Priseable is a new word, according to spellchecker, and I claim it! If we are priseable, we can be opened for a time. If we can be opened, we can make different choices, or enable others to do so. And this, maybe, is our working definition of real world cultural intelligence.

What’s in the kit bag?

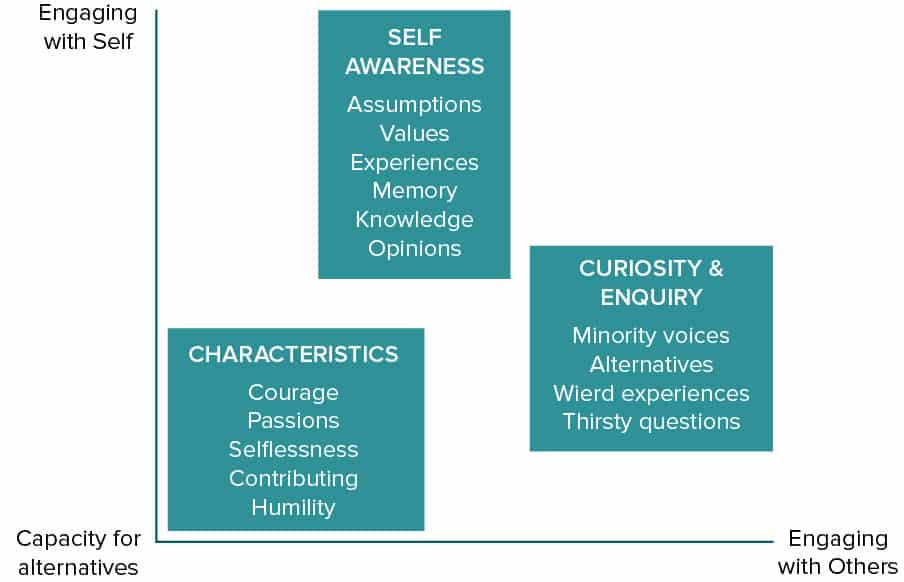

There are some important bits of kit that need to be put into our bag. These include some SELF AWARENESS of things we carry with us daily:

- Assumptions, taken for granted or unquestioned

- Values, with all their conflicts, for which we have, of course, solid reasons

- Experiences, with all their subjective post-event revisions

- Knowledge, things that we irrefutably ‘know’

- Opinions, substitutes or responses for things we think others irrefutably ‘know’ and we disagree with

- And so on.

You and I are riddled with these things, steeped in them. In this sense our ability to develop cultural intelligence, to be free albeit temporarily from the limitations of these things, is itself culturally bounded. Culture is cultured. Oh dear. Shake them up! A culturally intelligent person needs to know the limit of her or his limitations. Dig deep if you must but find the limit of your limits.

Into the bag, to help us out, go tools of CURIOSITY & ENQUIRY, to help us go beyond ourselves and take on:

- Minority voices, hearing, savouring, valuing, seeking them

- Alternative knowledge, things that test, challenge and alter our world view

- Weird experiences, things that encourage us to do or confront our prejudices and fears

- Questions, those we like asking, those we like hearing, especially enquiry oriented, thirsty questions, that feed refresh and grow us.

- And so on.

You and I are riddled with the potential for these things, yet we rarely indulge them. In organisations we are too busy with performance, compliance, common ‘values and purpose’ whilst at the same time promoting diversity and inclusion. We use easy heuristics to tackle complex problems; lists of preferred types of candidates, 2×2 boxes to provide quick and queasy typologies of our people; performance management that rewards or punishes individuals for outcomes in the full knowledge that all work inputs is completed by teams of people collaborating.

So, the final kit to go into our bag encompasses CHARACTERISTICS:

- Courage, to speak up and call out the things that are not fit for purpose

- Passion, for the flourishing of everyone! Not just our own reward, but equity for all

- Selflessness, the necessary, tough discipline of social resilience

- Humility, accepting that the answers, and the questions, lie with others too

- Contributing, to others, for others, to enable others.

Modelling cultural intelligence

I am guilty of something. I have offered no easy model and I have proposed no ‘do this and it’s all fixed!’ cures. I have offered a kit bag with three compartments, that all culturally intelligent organisations and leaders might need to take on board. In filling up the kit bag, I hope we are discovering a mix of three things:

| SELF AWARENESS: | Things you ought to own up to; not to others but to yourself first |

| CURIOSITY & ENQUIRY: | Things you have should engage with; in order to listen better and allow others to be heard |

| CHARACTERISTICS: | Things you should challenge yourself to share and show; because without them you are a spectator, and spectators don’t make a difference. |

The beginning of a model perhaps:

Whilst not intended to be exhaustive, this is stage one of a dialogue about cultural intelligence. Why is it important? I believe for two reasons:

In a world driven by the unregulated flow of opinion and ego packaged as wisdom and knowledge, humanity urgently needs to develop a counterflow of listening and engaging. The digitisation of prejudice is not progress. It appears to be narrowing minds, deepening the cult of self and undoing communities. This is not the fault of technology, it is the fault of content, and content is the responsibility of us all.

The effect of technology on work is already massive, and yet it is only at an early stage. If humanity has an advantage it is our potential for creative, imaginative quantum leaps. Our very illogicality is our great strength. Our education systems, organisations, and family and community traditions can either build or destroy these strengths and potentials. Letting them whither as an inevitable consequence of technology is dangerous. Nothing is inevitable until we collectively will or allow it to be so.

Cultural intelligence is important. It necessitates humility, a precious commodity. But from it can come people and organisations that flourish together for the benefit, welfare and good of us all. This is our mission at Roffey Park, as we seek to educate and contribute to inclusive, diverse and resilient human communities. Join with us and make it yours too.

References

Jowett, B. (ed.) (1941). Plato’s The Republic. New York: The Modern Library

Mann, M. (1986). The Sources of Social Power, Vol I: A History of Power from the Beginning to 1760 A.D. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Eggerman, M. & Panter-Brick, C. (2010). Suffering, hope and entrapment: Resilience and cultural values in Afghanistan: Social Science and Medicine: 71, pp 71-83.

Persson, I. (2018). The Fundamental Problem of Philosophy: Its Point. Journal of Practical Ethics, 6 (1), pp.52-68

Rajan, R. (2019). The Third Pillar: How Markets and The State Leave the Community Behind. New York: Penguin Press.